Dismissal of Charges Based on Unsoundness of Mind or Unfitness for Trial by Linda Cho

Dismissal of Charges Based on Unsoundness of Mind or Unfitness for Trial

Magistrates have the power to dismiss charges for simple offences if they are reasonably satisfied that the defendant is of unsound mind or unfit for trial.[1] A simple offence is a less serious offence, including some indictable offences, which can be dealt with by the Magistrates Court.[2] This power allows defendants to avoid the lengthy process in the Mental Health Court.

For example, the following charges (not limited to) may be dismissed by the Magistrate under this power:

- Public nuisance

- Assault or obstruct a police officer

- Drink driving

- Assault occasioning bodily harm

- Trespassing

The decision to dismiss charges

A person charged with an offence is of ‘unsound mind’ if they do not have the capacity to understand or control their actions, or know that they should not act in the manner constituting the offence.[3] This lack of capacity must arise primarily due to mental health or disability, even if the person was intoxicated at the time of the offence.[4] A person may be found unfit to plead and stand trial if they cannot understand the significance of telling the truth in court, comprehend the nature of the charge or instruct their solicitor.[5]

Reasonable satisfaction has not been defined by statute, but it is considered to mean ‘clear and convincing evidence’ is present to support the decision.[6] Magistrates are not restricted by the requirement that the dismissal must only occur in exceptional or extreme circumstances.[7]

In making a decision regarding dismissal, Magistrates may be provided a report from the Court Liaison Service outlining the defendant’s antecedents, mental health and cognitive disability.[8] Court Liaison Service is a part of Queensland Health and is a free service, however defendants may also engage independent experts to provide similar reports. If the person is unfit for trial but is likely to become fit within 6 months, the Magistrate may adjourn the hearing.[9]

Consequences of dismissal

If the Magistrate dismisses the charges, the person is discharged and cannot be further prosecuted for the relevant offending.[10]

Once the charge is dismissed, the Magistrate may refer the person to a disability services agency or the health department if they do not also have a mental illness.[11] The Magistrate can also make an ‘examination order’ if they are reasonably satisfied the person would benefit from being examined by an authorising doctor.[12] The doctor may then make or vary a treatment authority for the person and recommendations for the person’s voluntary treatment or care.[13] More information about treatment authorities can be found here.

This process is a useful tool for diverting people with mental illnesses and/or cognitive disability from the criminal justice system at an early stage. It assists the rehabilitation of offenders rather than simply punishing them where there are clear underlying issues to be resolved associated with their ‘criminal’ behaviour.

How Robertson O’Gorman can help

If you are unwell and cannot recall the circumstances around the alleged offending and/or have a mental health illness or cognitive disability Robertson O’Gorman can assist you by:

- Providing you with legal advice regarding your options, including applying for a dismissal of charges

- Assisting you in obtaining a report from the Court Liaison Service

- Referring you to an independent expert who can provide supporting documents for your application to dismiss your charges

- Corresponding with the prosecutor and advocating on your behalf in Court

Call us today on 3034 0000 or log an enquiry through our Free Case Appraisal.

[1] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) ss 22, 172; Magistrates Court Practice Direction No 1 of 2017.

[2] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) s 172; Justices Act 1886 (Qld) s 4.

[3] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) sch 2; Criminal Code (Qld) s 27.

[4] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) sch 2; Criminal Code (Qld) s 27; JKO v Queensland Police Service [2018] QMC 4.

[5] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) sch 2; R v Presser [1958] VR 45.

[6] RRK v Queensland Police Service [2019] QDC 176, [19].

[7] RRK v Queensland Police Service [2019] QDC 176, [17].

[8] Queensland Health, Court Liaison Service (Chief Psychiatrist Policy, 15 April 2020) 5

<https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/638454/cpp_court_liaison_service.pdf>.

[9] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) s 173.

[10] RRK v Queensland Police Service [2019] QDC 176, [18].

[11] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) s 174.

[12] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) s 177.

[13] Mental Health Act 2016 (Qld) s 177.

Part 1: Appeals Process in Queensland - Introduction, History and Queensland Process by Ella Scoles

Part 1 of a 3 part series explores the Appeals Process in Queensland. In this blog, we look at the history of the Appeals process and what happens in Queensland.

- Introduction

In Australia, the ability to seek relief from a criminal conviction comes in the form of a traditional post-conviction appeal, or, in very exceptional circumstances, through a pardon provision. These are both couched in state law.[1] While for a large amount of their histories, the various states and territories of Australia shared largely similar provisions relating to these two post-conviction limbs, more recently some discrepancies between the states have arisen. Traditionally, an Australian defendant (or appellant) only has one right of appeal, as is the case in Queensland, New South Wales, Northern Territory, Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory. However, after a long campaign, in 2013, 2015 and 2019 respectively, South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria enacted legislation to allow for a second, or subsequent, right of appeal.[2] There is also a bill currently before the Western Australian Parliament that, if passed, will introduce a subsequent right of appeal in that State.

- A history: The current appeals process generally

Australia’s historical experience with colonialism meant that each of Australia’s states and territories (eventually) adopted the United Kingdom’s ‘common form’ appeals provisions after their creation in 1907.[3] This is because under the Australian Constitution, each state and territory is granted the powers to administer their own criminal law.[4] Therefore, the ability to seek post-conviction relief (both through an appeal or a pardon provision) is confined by the parameters of each state or territory’s respective legislative provisions.[5] Importantly, the Australian post-conviction framework, as with all areas of the law, is grounded in the principle of finality. This dictates that once the court enters a perfected judgement that matter is over and may not be reopened except in narrow circumstances.[6] In this respect, as an appeals court must ‘not attempt to enlarge its jurisdiction beyond what Parliament has chosen to give’,[7] the Australian jurisdiction has interpreted the right of appeal to be restricted to one appeal only. This means that if an applicant has already exhausted their one appeal, no matter how compelling the ground of appeal or fresh exculpatory evidence may be, an appeals court simply cannot hear a new appeal. The adherence to the principle of finality is so rigid that even Australia’s highest court – the High Court – is unable to hear a secondary application from a person who has exhausted their appeals options but claims to be wrongfully convicted and has evidence to prove this.[8] While there is a power for a defendant to apply for special leave to hear their case in the High Court,[9] this leave is unfortunately incredibly difficult to obtain.[10] Even then, if fresh, exculpatory evidence comes to light, the High Court has maintained the view that it is not able to hear such evidence.[11]

- The Queensland appeals process

In Queensland, the criminal appeals process is governed by Chapter 67 of the Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) (‘the Queensland Code’). Under the Queensland Code a person convicted of an offence on indictment may appeal to the Court of Appeal either: against the person’s conviction on any question of law;[12] with the leave of the Court against the person’s conviction on a question of fact, a mixed question of fact and law, or any ground the Court considers appropriate;[13] or with the leave of the Court against the person’s sentence.[14] This must occur within one calendar month of the verdict’s delivery,[15] meaning that appeals are almost always built upon the evidence that was available at the original trial. If the appeal is not lodged within one month, an applicant is able to apply to the Court for an extension to this time limit,[16] however the Court is generally only inclined to approve this extension if the potential appellant can show good reason for the delay, or, that to deny the opportunity to appeal would result in an obvious miscarriage of justice.[17] The Court is encouraged to accept an appeal if the Court is of then opinion that: the verdict of the jury should be set aside on the ground that it is unreasonable, the verdict could not have be supported having regard to the evidence, the trial judgment should be set aside on the ground that it contained a wrong decision on a question of law, or if there was in anyway a miscarriage of justice.[18] However, notwithstanding the occurrence of a substantial miscarriage of justice, the Court is not bound to allow the appeal even if one of the grounds above are made out.[19] If an appeal is allowed, the Court of Appeal either orders a new trial in such manner as it thinks fit or quashes the conviction and directs a judgment and verdict of acquittal to be entered.[20] However, while in theory a ‘discretion exists’ that allows the Court of Appeal to acquit an appellant upon appeal, as opposed to ordering a retrial, Courts are generally reluctant to do so in an effort to not ‘usurp’ the functions of a jury.[21] Indeed, a Court of Appeal will ordinarily only enter a verdict of acquittal if it is ‘held that the case considered as a whole required a jury to acquit the appellant because it must entertain a reasonable doubt or that a conviction would necessarily be unsafe’.[22]

If, however, the traditional appeals process fails, and a person still maintains their innocence, then that person can appeal to the Queensland Governor for a pardon.[23] Couched in the discretionary power of the common law, these ‘petitions of mercy’ or ‘pardon’ provisions grant the Queensland Governor the ability to refer either some or the whole of the case to the Court of the Appeal.[24] If successful, a pardon does not erase the conviction in its entirety, instead it simply removes any punishments or penalties the person has endured or is enduring because of the conviction.[25] However, the context in which this unique post-appeals process operates is uncertain,[26] especially since the granting of pardons is exceptionally rare in Australia.[27] Generally, it is agreed that the discretion granted to the Governor is wider than that of a court in that they are ‘unconfined by any rules or laws of evidence, procedure, and appellate conventions and restrictions.’[28] Therefore, issues not usually available to courts to consider in their decision making process,[29] as well as sources of information that may not overcome the laws of evidence in criminal trials,[30] are able to be taken in account by the Governor.

[1] See the following for appeals provisions: Criminal Appeal Act 1917 (NSW) s 5(1); Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) s 668D(1); Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT) s 410; Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) s 352(1); Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas) s 401(1)(a); Supreme Court Act 1933 (ACT) s 37E; Criminal Appeals Act 2004 (WA) s 7; Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic) s 274; see the following for petitions of mercy provisions: Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) ss 16–22A; Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001 (NSW) ss 76–7; Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) s 584; Sentencing Act 1995 (WA) pt 19; Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas) s 419; Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT) s 431; Crimes (Sentence Administration) Act 2005 (ACT) pt 13.2.

[2] Criminal Code Amendment (Second or Subsequent Appeal for Fresh and Compelling Evidence) Act 2015 (Tas); Justice Legislation Amendment (Criminal Appeals) Bill 2019 (Vic); Originally the Statutes Amendment (Appeals) Act 2013 (SA) enacted s 353A of the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) which allowed for a subsequent right of appeal. On 5 March 2018 the Summary Procedure (Indictable Offences) Amendment Act 2017 commenced and section 11 of that Act repealed s 353A of the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA). Section 353A was re-enacted in identical form as Criminal Procedure Act 1921 (SA) s 159.

[3] See, eg, Mas Rivadavia v The Queen (2008) 236 CLR 358, 382 (French CJ), ‘it must be accepted that the question will ordinarily fall for consideration in the application of statutory language, in this case the common form provision for criminal appeals reflected in s 6(1) of the Criminal Appeal Act [1907 (UK)]’.

[4] Note that the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1901 (Cth) does not confer on the Commonwealth any express powers to legislate in regards to criminal law. While this does not completely bar the Commonwealth from creating criminal provisions, as all state constitutions have relevant powers allowing them to legislate on criminal matters, it has generally been accepted that states must create and administer their own criminal law, see Attorney-General’s Department, ‘The Constitution’, Federal Register of Legislation (Web Page, 1 January 2012) <https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2005Q00193> viii-ix; Justice Michael Kirby, ‘A New Right of Appeal as a Response to Wrongful Convictions: Is it Enough?’ [2019] 43 Criminal Law Journal 299, 299.

[5] See above n 1.

[6] See D’Orta-Ekenaike v Victoria Legal Aid (2005) 223 CLR 1 (‘D’Orta-Ekenaike’).

[7] R v Edwards (No 2) [1931] SASR 376, 380.

[8] Justice Michael Kirby, ‘A New Right of Appeal as a Response to Wrongful Convictions: Is it Enough?’ [2019] 43 Criminal Law Journal 299, 300.

[9][9] Contained in Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) s 35A.

[10] David Hamer, ‘Wrongful Convictions, Appeals, and the Finality Principle: The Need for a Criminal Cases Review Commission’ (2014) 37(1) UNSW Law Journal 270, 286.

[11] Mickelberg v R (1989) 167 CLR 259, 264, 298. This is owing to the High Court’s interpretation of the appellate powers conferred to it via the section 73 of the Australian Constitution. This appellate jurisdiction has been interpreted to exclude the original jurisdiction of states. Therefore, as fresh evidence requires ‘an independent and original decision’ to occur, and as this decision has been interpreted to fall within the remit of the jurisdiction of state courts, fresh evidence is not capable of being heard in the High Court. It should be noted that if a matter concerns fresh, exculpatory evidence the High Court does have the power to refer the matter back to the state courts to consider admitting that fresh evidence who then may refer the matter back once again to the High Court with this evidence admitted. However, this is unfortunately infrequently used, see Justice Kirby (n 8) 300.

[12] Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) (‘The Queensland Code’) s 688D(1)(a).

[13] Ibid s 688D(1)(b). There is also much debate over whether this requirement for leave is itself a deficiency of the Australian appeals process, see: Chris Corns, ‘Leave to Appeal in Criminal Cases: The Victorian Model’ (2017) 29(1) Current Issues in Criminal Justice 39. While the parameters of this essay mean that only the most prominent arguments relating to Australia’s post-conviction mechanisms can be discussed, this should still be noted as an area of debate.

[14] The Queensland Code ss 668E(3), 688D(1)(c), 671(1). Usually, this occurs on the basis the sentence was ‘manifestly inadequate’ in that the sentence was too harsh in light of the circumstances of the case. When an appeal is being made against a sentence, the Court of Appeal has the power to both increase or decrease the sentence if it is of the opinion that some other sentence is warranted at law and should have been passed.

[15] The Queensland Code s 671(1).

[16] Ibid s 671; Criminal Practice Rules 1999 (Qld) r 65(3) (Form 28).

[17] Caxton Legal Centre, ‘Appeal Against Conviction’ (Web Page, 21 December 2016) <https://queenslandlawhandbook.org.au/the-queensland-law-handbook/offenders-and-victims/court-processes-in-criminal-matters/appeals-against-conviction/>.

[18] The Queensland Code s 668E(1).

[19] Ibid s 668E(1A). There is also much debate over whether this ‘proviso’ allowing a court to effectively accept an error so long as it is not substantial is a major defect in Australia’s appeals framework, see: Catherine Penhallurick, ‘The Proviso In Criminal Appeals’ (2003) 27(3) Melbourne University Law Review 800. While the parameters of this essay mean that only the most prominent arguments relating to Australia’s post-conviction mechanisms can be discussed, this should still be noted as an area of debate.

[20] The Queensland Code ss 669, 668E(2).

[21] Martens v Commonwealth [2009] FCA 207, 127-8.

[22] Ibid 128.

[23] See above n 1.

[24] The Queensland Code s 672A.

[25] R v Foster [1985] QB 115, 118; Eastman v DPP (ACT) (2003) 214 CLR 318, 350-1.

[26] Sue Milne, ‘The Second or Subsequent Criminal Appeal, the Prerogative of Mercy and the Judicial Inquiry: The Continuing Advance of Post-Conviction Review’ (2015) 36(1) Adelaide Law Review 211, 217.

[27] See below n 94.

[28] Mallard v The Queen (2005) 224 CLR 125, 129.

[29] Such as public concern regarding the proprietary of the conviction, see: Mickelberg v R (1989) 167 CLR 259.

[30] Such as ‘reports in the media, a petition presented to Parliament, a representation from a parliamentary colleague, or perhaps hearsay evidence as to the reliability of a complainant’, see: Martens v Commonwealth [2009] FCA 207, 128-9.

Who is “the occupier” of a vehicle under section 129(1)(c) Drugs Misuse Act 1986 (Qld)? by Hannah Pugh

Who is “the occupier” of a vehicle under section 129(1)(c) Drugs Misuse Act 1986 (Qld)?

“The occupier” in section 129(1)(c)

Section 129(1)(c) of the Drugs Misuse Act 1986 (Qld) deems possession of drugs found at a premises on “the occupier” of that premises.

‘The occupier’ is not defined in the Act but rather is a question of fact determined on a case-by-case basis by the Courts.

The following points have been considered relevant to determining who “the occupier” is under section 129(1)(c):

- Ownership of the place where drugs are found is not enough to establish occupation of it.[1]

- Mere presence in a place is not enough to establish occupation of it. Rather, occupation is commonly treated as “being dependent upon control, in the sense of being able to exclude strangers”.[2] The occupier of a place will thus have the ability to exclude strangers from it.[3]

- The occupier of a place is distinguished from an occupier of a place. The occupier of a place will purport to exercise a right to exclude others from it. An occupier of a place does not purport to exercise that right.[4]

- The occupier of a place must make use of that place, and have sufficient control of the place to facilitate that use.[5]

- A person may be the occupier of only one part of a place.[6]

“The occupier” of a vehicle?

A vehicle is a ‘place’ under section 129(1)(c)[7] and as such, the same factual considerations apply to the question of occupancy.

In R v P[8] two men, ‘N’ and ‘P’, were charged with possession of drugs found in a parked van. The van was parked at P’s house. N had the keys to the van and admitted to owning it. CCTV footage however showed both men travelling in the van before it was parked at P’s house. Specifically, the footage showed that P drove the van before it was parked. N’s possession of the keys indicated that N took over driving at some point before the van was parked. In coming to the conclusion that P had “at least joint control” of the van, Justice Applegarth referred to the evidence of P driving it as being P’s “earlier presence and control of the van”.[9]

In R v Sellwood[10] police intercepted a car whilst it was parked in a driveway. The appellant was the driver of the car. A second man was in the passenger seat of the car and had been in the car for about 30 seconds before police interception. Drugs were found “leaning against the center console of the car… on the hump, just more over to the passenger side… but leaning against the center console itself”.[11] The passenger was found with a significant amount of cash on him. The inference was that there was to be a drug deal. The driver of the car was found to the occupier of the car. This finding was upheld on appeal.

Conclusion

R v P[12] and R v Sellwood[13] seem to suggest that the starting point to an inquiry of this kind is that the driver, not the passenger, will be deemed “the occupier” of a vehicle.

Although the question of occupancy will turn on the individual facts of a case, taking into account the elements of use and control as outlined above, this appears the logical starting point.

[1] R v Smythe (1997) 2 QR 223.

[2] Thow v Campbell [1996] QCA 522 at 5, citing Council of the City of Newcastle v Royal Newcastle Hospital (1959) 100 CLR 1 at 4.

[3] Thow v Campbell [1996] 522; R v Ma [2019] QCA 1.

[4] R v Straker [1997] QCA 113 at 5.

[5] Ibid at 8.

[6] R v Smythe (1997) 2 QR 223.

[7] Drugs Misuse Act 1986 (Qld), s 4.

[8] R v P [2016] QSC 050.

[9] At [26].

[10] [2011] QCA 70.

[11] At [4].

[12] [2016] QSC 050.

[13] [2011] QCA 70.

PPRA and Non-Recording of Evidence - R v Jeffers and Morcom by Ella Scoles

INTRODUCTION

The Supreme Court of Queensland recently published an interesting pre-trial ruling in relation to the admissibility of improperly-obtained evidence.

In R v Jeffers and Morcom [2020] QSCPR 29 the Supreme Court exercised its discretion to exclude evidence that fell short of the legislative requirements in the Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000 (Qld) (‘the PPR Act’).

This case concerned two co-defendants, Mr Morcom and Mr Jeffers. They stood accused of attempted murder and burglary at the dwelling of Alan Kevin Black.

On the 25th of January 2018, Mr Black was attacked and seriously wounded. One of the wounds inflicted was a cut to his throat. He was also stabbed.

Mr Black passed away from unrelated matters prior to the matter being heard before the Court.

The Defence wished to exclude three separate conversations Mr Jeffers had with police. Each of these conversations contained various inculpatory admissions made by Mr Jeffers. The relevant conversation, for which the Court exercised its discretion to exclude evidence, concerned a conversation between Mr Jeffers and two Police Officers. The conversation occurred in the ‘administration area’ of the Nambour Police Station.

Whilst other police were interviewing Mr Morcom, Mr Jeffers remained in the company of the two Officers. Both of those Officers said that, at this point, Mr Jeffers volunteered: ‘Okay. I am going to tell you everything. I stabbed him. I stabbed him to teach a lesson for poisoning me…’

It was alleged he then went on to explain in detail how and why he poisoned Mr Black. This included details as to the amount of pressure used to wound the victim’s neck as well as the strategic placement of the stab wounds on Mr Black’s body.

This conversation was not recorded by the Officers involved. In one Officer’s case, a record of the conversation was constructed two days after the events. The other’s was not made till two months after the alleged conversation. At no point was the occurrence of this conversation put to Mr Jeffers nor was anything supposedly said in conversation endorsed by him.

Of importance, the Officers involved asserted that this conversation took the form of a monologue and did not involve a single question being asked by them.

WHAT DOES THE LAW SAY – THE OBLIGATIONS OF POLICE REGARDING CONFESSIONS AND INTERVIEWS OF SUSPECTS AND THE CONSEQUENCES OF A BREACH

By virtue of the PPR Act, police officers have certain obligations they must adhere to when conducting their duties. One such obligation is that all questioning of a relevant person (including a suspect) must be electronically recorded if practicable (section 436 of the PPR Act). If electronic recording is not practicable, police must arrange for any confession or admission of guilt to be recorded in writing (section 437 of the PPR Act).

Other safeguards (e.g. the presence of support people) are included in the PPR Act to regulate police questioning of indigenous people (section 420 of the PPR Act), children (s 421 of the PPR Act), people with impaired capacity (s 422 of the PPR Act) or intoxicated persons (s 423 of the PPR Act).

What if police fail to adhere to these obligations?

Section 130 of the Evidence Act 1997 (Qld) preserves the court’s common law ability to exclude evidence from a criminal proceeding if they are satisfied that it would be unfair to that person to admit the evidence. The common law test in the context of admissions is that, in determination of all the circumstances of the case, something is unfair if:

- There is an unacceptable risk that the jury may use the evidence prejudicially; and

- The evidence is not probative (i.e. reliable).

Central to the fairness discretion is the right of an accused to a fair trial. The relationship between these two concepts was discussed in depth by the High Court in Dietrich v The Queen (1992) 177 CLR 292:

The expression ‘fair trial according to law’ is not a tautology. In most cases a trial is fair if conducted according to law, and unfair if not. If our legal processes were perfect that would be so in every case. But the law recognizes that sometimes, despite the best efforts of all concerned, a trial may be unfair even though conducted strictly in accordance with law. Thus, the overriding qualification and universal criterion of fairness!

Speaking generally, the notion of "fairness" is one that accepts that, sometimes, the rules governing practice, procedure and evidence must be tempered by reason and common sense to accommodate the special case that has arisen because, otherwise, prejudice or unfairness might result.

It should be noted that there is much debate over both the kind of evidence the discretion applies to as well as the scope of the discretional test.

By contrast, it is generally accepted that evidence beyond that of confessions/admissions (i.e. what is deemed ‘real evidence’) cannot be excluded solely on considerations of fairness to the accused. Rather, this evidence is excluded if it overcomes the ‘public policy’ test. This requires the balancing of two competing considerations: the desirable goal of bringing wrongdoers to conviction, against the undesirable effect of curial approval or even encouragement being given to unlawful conduct of law enforcement officers.

It is clear that each of these discretions overlap considerably, despite them being separate powers capable of being enlivened by the court.

THE DECISION OF THE COURT IN R V JEFFERS AND MORCOM

In deciding the application before the court, Callaghan J noted that judgement of R v Swaffield; Pavic v R [1998] HCA 1 was particularly applicable to the circumstances. Particularly, [91] states:

In the light of recent decisions of this Court, it is no great step to recognise, as the Canadian Supreme Court has done, an approach which looks to the accused’s freedom to choose to speak to the police and the extent to which that freedom has been impugned. Where the freedom has been impugned, the Court has a discretion to reject the evidence. In deciding whether to exercise that discretion, which is a discretion to exclude not to admit, the Court will look at all the circumstances. Those circumstances may point to unfairness to the accused if the confession is admitted. There may be no unfairness involved but the Court may consider that having regard to the means by which the confession was elicited, the evidence has been obtained at a price which is unacceptable having regard to prevailing community standards. This invests a broad discretion in the court but it does not prevent the development of rules to meet particular situations

Callaghan J noted that the above consideration clearly arises in circumstances where police officers are required to electronically record conversations such as the one in question under the Act.

While the Prosecution sought to excuse the failure to electronically record the conversation on the basis that Mr Jeffers was not officially being ‘questioned’ by police, Callaghan J rejected this argument. He reasoned that ‘there is nothing about Mr Jeffers or his speech pattern which suggests that he might have delivered a confessional soliloquy of the kind suggested’.

Thus, it was held the conversation alleged to have occurred was one that came under the remit of the Act and therefore should have been recorded. The Court was also not prepared to accept that the breach of the Act was justified, stating that ‘the failure to record the conversation defied elementary common sense’. While His Honour noted that there may have been some reasonable delay at the beginning of the conversation and it would have been acceptable for this to go unrecorded, ‘once [Mr Jeffers] embarked upon the exercise of telling police about his involvement in the attack on Mr Black, anyone who was concerned to ensure the reliability of any evidence to be given about those admissions ought to have started making a record of some kind. There were plenty of options available in the circumstances - all parties were in a police station’.

CONCLUSION

Excluding improperly obtained admissions to police is a complex and intellectually challenging task.

R v Jeffers and Morcom [2020] QSCPR 29 provides an example of when a departure by police from their lawful obligations will attract the court’s discretion for exclusion. It adds to the mountainous jurisprudence of this complicated and difficult area of evidentiary law.

Restorative Justice Series – Part 3. Restorative Justice Processes

Restorative Justice Series – Part 3. Restorative Justice Processes

The previous instalment in this series discussed juvenile sentencing principles and sentencing options. Particular emphasis was placed on the breadth of available sentencing options for courts that are aimed at rehabilitating children and diverting them from the criminal justice system.

This blog will look specifically at restorative justice processes, their aims and consequences. Both police and court referrals to restorative justice processes will be discussed.

Background

Restorative justice is an internationally recognised response to criminal behaviour where the impact on society, and harm caused to the victim, family relationships and community are considered in depth. This is opposed to viewing criminal behaviour as simply an act of breaking the law, and represents a more holistic approach to justice.

A restorative justice conference is a meeting between a child who has committed a crime and the people most affected by the crime to discuss what happened, the effects of the offence, and how best to repair the harm caused to the victim. This requires active participation by the child, distinguishing the process from traditional justice responses.

The central purpose of this process is to provide a safe environment for everyone involved to talk about what happened and steps that can be taken to better things.

The restorative justice process can be entered at two stages:

- If a police officer refers an offence for the process after a child admits to committing the offence

- If the court refers an offence for the process after a child pleads guilty in court, or a child is found guilty after they pleaded not guilty

Police diversion

If a child admits to an offence and is willing, police officers can refer them to a voluntary conference or an alternative diversion program (see below regarding alternative diversion programs).[1] Police have wide discretion as to which offences they can refer to the restorative justice process. Referrals can be made if:[2]

- The child indicates a willingness to comply with the referral

- A caution is inappropriate

- The restorative justice process would be more appropriate than prosecuting the child

- The nature of the offence

- The harm suffered by anyone because of the offence

- Whether the interests of the community and the child would be served by having the offence considered or dealt with through a restorative justice process.

Prior to engaging in the process, the police must inform the child about the process and the consequences if they fail to participate properly. The restorative justice process is run by an independent and accredited convenor. The aim of the conference is for the child and other concerned persons to consider or deal with the offence in a way that benefits all concerned.[3]

The following people are allowed to attend and participate in the conference:[4]

- The child

- The victim

- The convenor

- The child’s parent

- At the child’s request, their lawyer, an adult member of their family or another adult

- If requested by the victim, the victim’s lawyer, an adult member of their family or another adult

- Another person approved by the convenor

The conference process involves a discussion of the offence, the impact and consequences for those affected, and the ways in which the child can repair the damage or harm caused to the victim. The convenor’s role is to ensure a fair outcome is reached for all parties and that no undue influence or pressure is put on anyone.

Court referral or order

Courts may refer children to the restorative justice process when:

- Dismissing the charge entirely when a child pleads guilty but applies for dismissal on the basis that police should have referred them to restorative justice

- Considering referral instead of sentencing if a child pleads guilty (this is required under the Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld))[5]

- Considering referral if the child is found guilty (this is required under the Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld))[6]

- Sentencing the child, such that attending a restorative justice process is considered to be a supervised community-based order (for more information on available orders, read the previous blog in the series)[7]

In considering whether a referral is appropriate, the court must consider: [8]

- The nature of the offence

- Harm suffered by anyone because of the offence

- Whether interests of the community and the child would be served at the restorative justice conference

Prior to making the referral, the court must also be satisfied that:

- The child has been told about and understands the process, and has agreed to participate

- The child is a suitable person to participate in the process

All other elements of restorative justice processes when ordered or referred by the court are the same as outlined above.

Consequences of restorative justice conferences

Conferences are conducted on a ‘without prejudice’ basis, meaning anything said during the conference cannot be used outside it or in any legal proceeding.[9] This means that anything said by the defendant cannot be used against them in a criminal proceeding against them.

If the conference is successful, a restorative justice agreement may be made. This may involve:

- Making an apology to the victim, orally or in writing

- Performing voluntary or community work

- Repair of or payment for any damage caused

The convenor must ensure that the agreement is not unreasonable or more onerous than if a court had dealt with the matter.

Police diversion

If the conference is successful, the child cannot be prosecuted for the offence unless the Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld) states otherwise.[10] However, if the conference is not successful or if the child breaches the restorative justice agreement made at the conference, the police can:[11]

- Take no action

- Caution the child

- Refer the offence to another restorative justice process

- Start a court proceeding against the child for the offence.

Court order or referral

If the referral is made by a court and the child does not complete the agreement, the matter must be brought back to the court. The court may then take no further action, allow more time for the child to comply with the agreement, or sentence the child. If the child does not participate, denies responsibility, or an agreement cannot be reached, the matter must be brought back to court for sentence.

Where the court referred the child to restorative justice conferencing to assist in sentencing, a copy of the agreement and information regarding the child’s compliance must be given to the court so that it can be taken into account in the sentence.[12] The court can then order that the child comply with the remainder of the agreement, and this can become whole or part of the sentence.[13]

Alternative diversion programs

Alternative diversion programs are available where a conference is not possible even if the child responsible is willing to participate. Referrals can be made in the same process as restorative justice conferences. The program is similarly used to help children understand the harm caused and take responsibility for the offence through various activities, including:[14]

- Remedial actions

- Activities to strengthen the child’s relationship with their family or community, and

- Educational programs.

The program must be designed to help the child to understand the harm caused by their behaviour, and allow the child an opportunity to take responsibility for the offence committed by the child.[15] The program must also ensure the child is not treated more severely for the offence than if the child were sentenced by a court or in a way that contravenes youth sentencing principles.[16] Finally, this program must be in writing and be signed by the child.[17]

Alternative diversion programs are conducted on a ‘without prejudice’ basis, meaning anything said during the program cannot be used outside it or in any legal proceeding.[18] This means that anything said by the defendant cannot be used against them in a criminal proceeding against them.

Family and community involvement

In keeping with the objectives of the Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld), restorative justice processes encourage families of child offenders to actively participate in the conference, help both their child and the victim understand each other and the consequences of their actions, and identify ways to help their child avoid trouble in the future.

Restorative justice processes also allow for cultural and community input to ensure the conference is appropriate to the specific community. For example, members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander local justice groups or community elders may be invited to participate.

This recognises the role of families and communities in ensuring children feel safe, a sense of belonging and connection, and respected.

Conclusion

The restorative justice process provides for effective means of diverting children from the criminal justice system while ensuring children take responsibility for their actions and victims feel heard and respected.

The effectiveness of this process is evident given 77% of children and young people who engaged in the program did not re-offend or showed a decrease in the magnitude of their re-offending.[19] 89% of victims were also satisfied with the outcome of the conference, and 70% believed the process would help them manage the effects of crime.[20]

Lawyers must understand how the restorative justice process operates and ensure that juvenile clients are provided with sufficient information and support in deciding whether to utilise the process.

[1] Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld) ss 31(2)-(3) (‘YJ Act’).

[2] YJ Act ss 22(3)-(4).

[3] YJ Act s 33.

[4] YJ Act s 34(1).

[5] YJ Act s 162(1).

[6] YJ Act s 162(2).

[7] YJ Act s 175(1)(db).

[8] YJ Act s 163, 192A.

[9] YJ Act s 40.

[10] YJ Act s 23(2).

[11] YJ Act s 24(3).

[12] YJ Act s 165.

[13] YJ Act s 175(1)(da).

[14] YJ Act s 38(1).

[15] YJ Act s 38(2).

[16] YJ Act s 38(3).

[17] YJ Act s 38(4).

[18] YJ Act s 40.

[19] Queensland Government, Youth Justice Strategy 2019-2023 (2021) 9 <https://www.cyjma.qld.gov.au/resources/dcsyw/youth-justice/reform/strategy.pdf>.

[20] Ibid.

The Sovereign Citizen Dilemma by Ella Scoles

Solicitor Ella Scoles writes about the Sovereign Citizen Dilemma in this QLS Proctor article:

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about a myriad of challenges to our legal system – balancing human rights, substantive and procedural law reforms, an uptake in remote appearances and maintaining access to justice for vulnerable Queenslanders in the face of this dramatic change. Perhaps one of the more distracting consequences of the pandemic has been the increasing frequency in which ‘sovereign citizen’ arguments are being mounted against our law enforcement officials and in courts.

Regard the full article here: https://lnkd.in/geRvNGjD

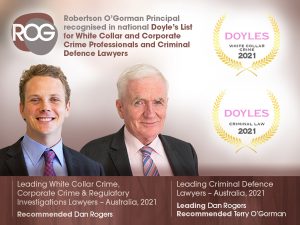

Robertson O’Gorman Principal recognised nationally in 2021 Doyle’s List for White Collar and Corporate Crime Professionals and Leading Criminal Defence Lawyers

Robertson O’Gorman Principal recognised nationally in 2021 Doyle’s List for White Collar and Corporate Crime Professionals and Leading Criminal Defence Lawyers

The Doyle’s Guide is an independent organisation that rates and recommends law firms and individuals based on interviews with clients, peers, and relevant industry bodies.

The Doyle’s 2021 rankings are in and we congratulate our Principal, Dan Rogers for being recognised nation-wide as Leading in the Leading Criminal Defence Lawyer Category (Australia), in addition to national recognition in the White Collar Crime, Corporate Crime and Regulatory Investigations Category (Australia).

Congratulations also to Terry O'Gorman; another one of our team awarded nation-wide recognition as a Recommended - Leading Criminal Defence Lawyer (Australia). All of the solicitors at Robertson O’Gorman strive for quality and superior customer service and we are very proud of their commitment to excellence.

An analysis of the Bill Cosby decision by Ella Scoles

Yesterday the world learnt that Bill Cosby’s conviction for three counts of aggravated indecent assault was overturned by the Pennsylvanian Supreme Court. In essence, the Court ruled that ‘when a prosecutor makes an unconditional promise of non-prosecution, and when the defendant relies upon that guarantee to the detriment of his constitutional right not to testify, the principle of fundamental fairness that undergirds due process of law in our criminal justice system demands that the promise be enforced’.

To make sense of that ruling, we must delve into the history of the Cosby matter.

In 2005, Montgomery County District Attorney (‘DA’) Bruce Castor learned that Andrea Constand had reported that William Cosby had sexually assaulted her in 2004. In evaluating the likelihood of a successful prosecution of Cosby, the DA foresaw difficulties with Constand’s credibility as a witness based, in part, upon her decision not to file a complaint promptly. Other foreseeable issues also included the fact that there no corroborating evidence to Constand’s accusations. Because of these considerations, DA Castor concluded that there was insufficient credible and reliable evidence to charge Cosby. This was, unless he confessed.

Running alongside this criminal complaint was also a civil action. Like in criminal trials, a witness or accused is open to prosecution for the crime of perjury if they lie during a civil hearing.

In the United States, when a deposition is taken in a civil case, the Constitutional right against self-incrimination allows a witness to refuse to answer any questions that might lead to criminal liability. But if there is no possibility of a criminal prosecution, then an individual cannot invoke that right and must answer questions. Cosby relied upon the DA’s declination and proceeded to provide four sworn depositions. During those depositions, Cosby made several incriminating statements.

However, DA Castor’s successors did not adhere to his decision not to prosecute, and decided to pursue Cosby notwithstanding that prior undertaking. Those inculpatory admissions were used in the subsequent criminal action against Cosby. The Supreme Court held that because Cosby had relied upon the undertaking of DA Castor, and that this reliance was ultimately to his detriment, to deny him the benefit of that undertaking was an ‘affront’ to the fundamental notion of fairness in a criminal trial. On that basis the Supreme Court vacated Cosby’s conviction and sentence.

Obviously, the decision is a thought provoking one. It suggests that when an accused suffers detriment due to a promise of a prosecutor, and that detriment is contrary to a longstanding legal doctrine such as the right to silence, the conviction itself may be unsound. This is not to say that the fact of the accused’s guilt is in question. Rather, the conviction was unsafe due to the process through which the inculpatory evidence was obtained.

In Australia, the jurisprudence concerning what constitutes an unsatisfactory or unsafe conviction is vast. While the Cosby decision is no doubt limited by the unique constitutional position of the United States, it's relevance to the Australian jurisdiction, at the very least, demonstrates the fundamental importance the common law legal system places in long cherished principles such as fairness and the right to silence.

QLS Proctor article on Terry O’Gorman AM: President’s Medal recognises a leader in criminal defence and civil liberties

John Teerds, Editor, writes about a highlight of last week’s Legal Profession Dinner being the presentation of the Queensland Law Society President’s Medal to leading criminal defence lawyer and civil libertarian Terry O’Gorman AM. QLS President Elizabeth Shearer told guests that Terry had been admitted to practice in 1976 and had worked fiercely to defend clients and to tirelessly protect the civil liberties of Queenslanders. He had sat on the QLS Criminal Law Committee since 1979 and was an Executive Member of the National Association for Criminal Lawyers since its inception in 1986. Terry was awarded the Order of Australia in a General Division in 1991 for services to the legal profession and holds the positions of President of the Australian Council of Civil Liberties and Vice President of the Queensland Council of Civil Liberties. He is also a QLS accredited criminal law specialist and Senior Counsellor, and was the winner of QLS’s 2020 Outstanding Accredited Specialist Award.

In his speech, Terry highlighted that a key criminal law challenge was explaining to the community that the fundamentals of criminal law had to be maintained at all costs, particularly presumption of innocence. “While there are going to be controversies from time to time – such as the current controversy about sexual assault – and while those controversies will have to be addressed, and properly addressed, it cannot be at the expense of the fundamentals of the criminal law, including the presumption of innocence and a fair trial,” he said.

A well-deserved award for an outstanding career in the field of criminal law - the full article is here.

Terry O’Gorman AM awarded QLS President’s Medal

Robertson O’Gorman Solicitors are delighted to announce, Senior Consultant, Terry O’Gorman has been awarded the prestigious President's Medal by the Queensland Law Society. This award was presented at the QLS Legal Profession Dinner at the Sofitel on Friday night.

Terry O’Gorman AM, Senior Consultant, Robertson O’Gorman Solicitors was admitted to practice in 1976 and has sat on the Queensland Law Society Criminal Law Committee since 1979. Terry has been involved in high profile criminal cases, including acting for a number of individuals in the wake of the Fitzgerald Inquiry. Terry was awarded the Order of Australia in a General Division in 1991 for services to the legal profession and holds the positions of President, Australian Council of Civil Liberties and President/Vice President, Queensland Council of Civil Liberties. He is also an accredited criminal law specialist.

Lawyers have a special responsibility for upholding the rule of law. The President's Medal distinguishes an individual at the pinnacle of their career who goes above and beyond to uphold the core values of our profession. This award recognises an experienced legal practitioner who has shown great integrity, courage, and responsibility through their commitment to continual improvement of the profession and of themselves. The nominees are judged on their legal competence, service to the community, personal integrity and professional commitment beyond the call of duty. It is a very fitting that Terry’s admirable and long-standing contribution to the legal profession has been recognised by this award. Congratulations Terry!